To me, the world of perfect forms is primary (as was Plato’s own belief) — its existence being almost a logical necessity — and both the other two worlds are its shadows.

Sir Roger Penrose, born on August 8, 1931, in Colchester, Essex, England, is a luminary in the realm of mathematical physics. His journey began with a Ph.D. in algebraic geometry from the University of Cambridge in 1957, and his career has spanned numerous prestigious posts at universities in both England and the United States. His work in the 1960s on the fundamental features of black holes, celestial bodies of such immense gravity that nothing, not even light, can escape, earned him the 2020 Nobel Prize for Physics. This recognition, shared with American astronomer Andrea Ghez and German astronomer Reinhard Genzel, is but a single star in the constellation of his achievements.

Penrose’s work on black holes, in collaboration with Stephen Hawking, led to the groundbreaking discovery that all matter within a black hole collapses to a singularity, a point in space where mass is compressed to infinite density and zero volume. This revelation illuminated our understanding of these enigmatic cosmic entities. His work did not stop at the theoretical; he also developed a method of mapping the regions of space-time surrounding a black hole, known as a Penrose diagram. This tool allows us to visualize the effects of gravitation upon an entity approaching a black hole, providing a window into the heart of these celestial mysteries.

In the second phase of his career, Penrose turned his gaze from the cosmos to the mind, delving into the enigma of consciousness. His philosophical explorations led him to argue that quantum mechanics, the theory that describes the behavior of particles at the smallest scales, is needed to explain the conscious mind. This perspective, as revolutionary as his work on black holes, was detailed in his books “The Emperor’s New Mind” (1989) and “Shadows of the Mind” (1994).

In his book “The Emperor’s New Mind”, Penrose uses Gödel’s incompleteness theorem to argue that human minds can perform tasks that no algorithm can. Gödel’s theorem states that there are truths within mathematical systems that cannot be proven within those systems. Penrose extrapolates this to suggest that human consciousness is capable of understanding and knowing truths that are fundamentally unreachable by algorithmic processes.

This perspective challenges the dominant computational theory of mind, which views the brain as a complex computer and consciousness as a product of computation. Instead, Penrose’s work suggests a deep connection between the mysteries of consciousness and the mysteries of quantum physics, opening up new avenues for understanding the nature of consciousness.

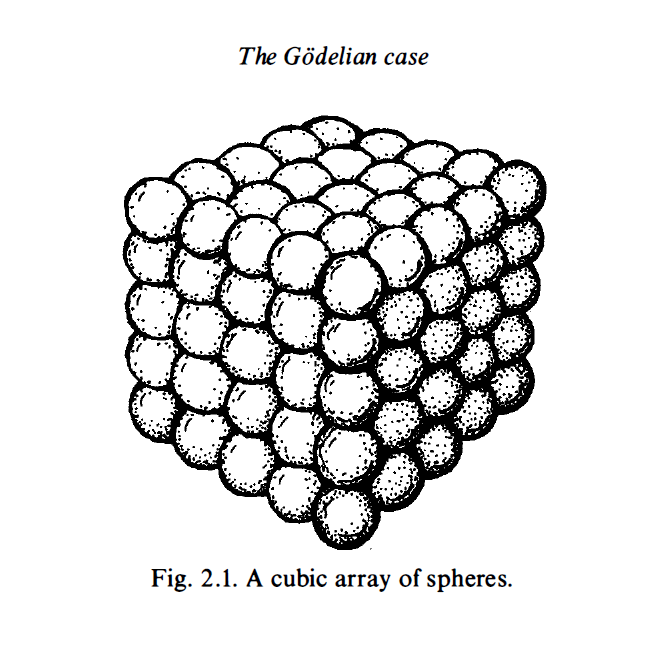

Within Penrose’s chapter, “The Godelian Case” (from “The Road to Reality”) the profound implications of Kurt Gödel’s incompleteness theorems are examined in relation to the connection between mathematics and geometry. Specifically, Penrose’s attention centers on the model depicted in Figure 2.1, which portrays a cubic array of spheres. Through this visual representation, Penrose explores the intricate relationship between geometry and mathematical understanding.

By introducing the model of a cubic array of spheres, Penrose highlights the fundamental role of spatial arrangements in mathematical cognition. This geometrical structure serves as a metaphorical embodiment of mathematical concepts, illustrating how spatial configurations can stimulate cognitive processes and facilitate intuitive comprehension of mathematical truths. The intricate interplay between the arrangement of spheres within the model and the underlying principles of mathematics encourages contemplation on the deep-rooted connections between geometry, spatial reasoning, and abstract mathematical thought.

Penrose’s utilization of the cubic array of spheres underscores his broader philosophical framework, which challenges reductionist accounts of human cognition that rely solely on formal systems or computational models. Through this geometrical representation, Penrose advocates for a more holistic understanding of mathematical insight, one that recognizes the essential role of geometric intuition in shaping human understanding. By delving into the intricate connection between mathematics and geometry, Penrose prompts a reevaluation of the mechanistic view of cognition, emphasizing the need to incorporate spatial reasoning and intuitive geometrical understanding into comprehensive models of human thought.

(E) Find a sum of successive hexagonal numbers, starting from 1 , that is not a

— Roger Penrose, Shadows of the Mind, p. 89

cube.

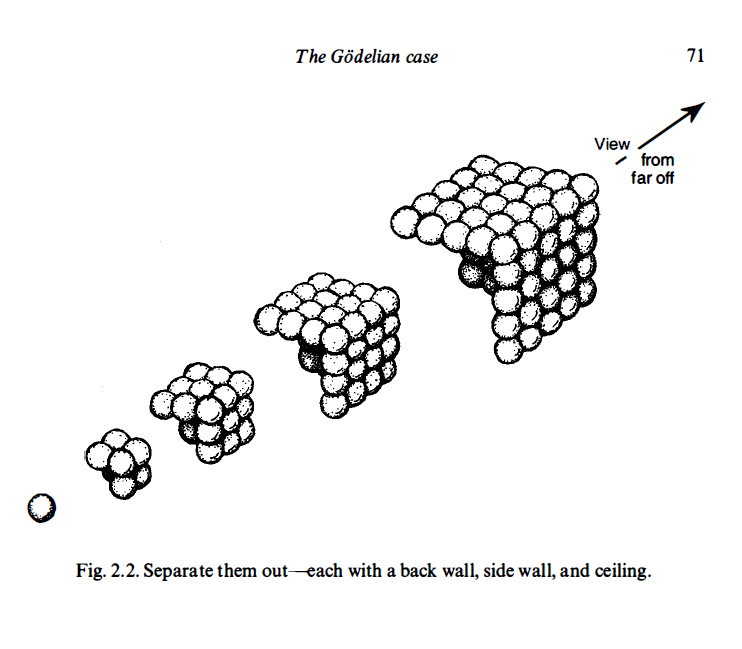

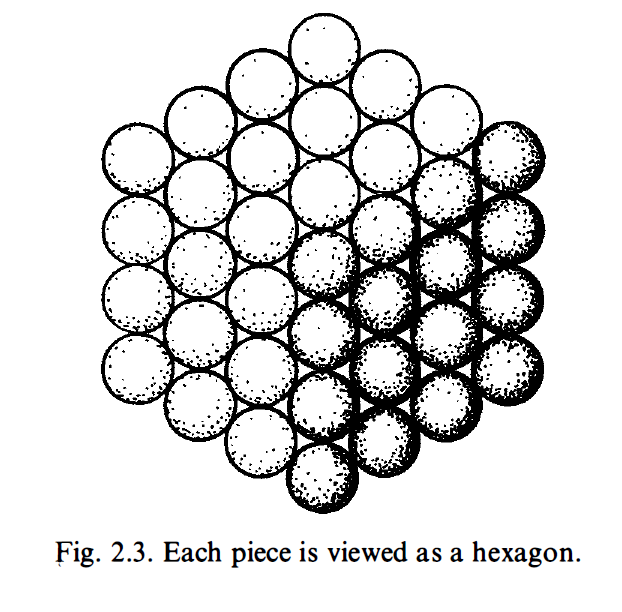

I am going to try to convince you that this computation will indeed continue for ever without stopping. First of all, a cube is called a cube because it is a number that can be represented as a cubic array of points as depicted in Fig. 2. 1 . I want you to try to think of such an array as built up successively, starting at one corner and then adding a succession of three-faced arrangements each consisting of a back wall, side wall, and ceiling, as depicted in Fig. 2.2. Now view this three-faced arrangement from a long way out, along the direction of the corner common to all three faces. What do we see? A hexagon as in Fig. 2.3. The marks that constitute these hexagons, successively increasing in size, when taken together, correspond to the marks that constitute the entire cube. This, then, establishes the fact that adding together successive hexagonal numbers, starting with 1 , will always give a cube. Accordingly, we have indeed ascertained that (E) will never stop.

Penrose’s work is characterized by a profound appreciation for geometry. His father, a biologist with a passion for mathematics, introduced him to the beauty of geometric shapes and patterns at a young age. This early exposure to geometry shaped Penrose’s unique approach to scientific problems, leading him to develop new mathematical notations and diagrams that have become indispensable tools in the field. His creation of the Penrose tiling, a method of covering a plane with a set of shapes without using a repeating pattern, is a testament to his innovative thinking and his deep understanding of geometric principles.

His fascination with geometry extended beyond the realm of mathematics and into the world of art. He was deeply influenced by the work of Dutch artist M.C. Escher, whose intricate drawings of impossible structures and infinite patterns captivated Penrose’s imagination. This encounter with Escher’s art led Penrose to explore the interplay between geometry and art, culminating in his own contributions to the field of mathematical art. His work in this area, like his scientific research, is characterized by a deep appreciation for the beauty and complexity of geometric forms.

In the realm of geometric cognition, Penrose’s work has the potential to make significant contributions. His unique perspective on the role of geometry in understanding the physical world, the mind, and even art, offers a fresh approach to this emerging field. His belief in the power of geometric thinking, as evidenced by his own groundbreaking work, suggests that a geometric approach to cognition could yield valuable insights into the nature of thought and consciousness.

The universe, in Penrose’s view, is a grand geometric tapestry, woven from the threads of mathematics and physics. Each thread, whether it represents a black hole, a conscious mind, or a geometric pattern, is part of a larger pattern, a cosmic design that we are only beginning to comprehend. His work points us in the direction of this grand design, inviting us to explore the intricate patterns and structures that make up our universe.

Objective mathematical notions must be thought of as timeless entities and are not to be regarded as being conjured into existence at the moment that they are first humanly perceived.

― Roger Penrose, The Road to Reality: A Complete Guide to the Laws of the Universe

In his later work on consciousness, Penrose has proposed that the brain’s ability to understand and manipulate geometric structures may be linked to quantum processes occurring within neurons. This idea, known as Orchestrated Objective Reduction (Orch OR), suggests that consciousness arises from quantum computations occurring within microtubules in brain cells. These computations, according to Penrose, are non-algorithmic and involve the manipulation of geometric structures at the quantum level.

I argue that the phenomenon of consciousness cannot be accommodated within the framework of present-day physical theory.

― Roger Penrose, The Emperor’s New Mind: Concerning Computers, Minds, and the Laws of Physics

Penrose’s Orch OR theory is like a bridge between two seemingly disparate worlds: the physical world of neurons and the immaterial world of conscious experience. This bridge, constructed from the building blocks of quantum mechanics, offers a path for us to traverse these two worlds, to explore the mysterious landscape of the mind from the vantage point of the physical brain. It is a journey that promises to reveal new insights into the nature of consciousness, the most enigmatic phenomenon in the universe.

His theory posits that consciousness arises from quantum computations within the brain’s neurons. This bold hypothesis, bridging the gap between the physical and the mental, has sparked intense debate and research in the scientific community.

For the field of geometric cognition, Penrose’s work can serve as map, charting a course through the complex terrain of the mind. His unique approach to visualizing complex mathematical and physical concepts provides a model for how we might navigate this terrain, how we might use geometric thinking to understand the workings of our own minds. It is a map that promises to guide us towards new discoveries, new insights into the nature of thought and understanding.

Not only because Roger Penrose’s contributions to the field of geometric cognition are deeply intertwined with his unique perspective on the nature of reality and consciousness, but his work has consistently emphasized the importance of geometry and topology in understanding the fundamental structure of the universe — a perspective that extends to his views on cognition as well.

Penrose’s work on twistor theory, a geometric framework that seeks to unify quantum mechanics and general relativity, is a testament to his belief in the primacy of geometric structures. This theory, which represents particles and fields in a way that emphasizes their geometric and topological properties, can be seen as a metaphor for his views on cognition. Just as twistor theory seeks to represent complex physical phenomena in terms of simpler geometric structures, Penrose suggests that human cognition may also be understood in terms of fundamental geometric and topological structures.

This perspective has significant implications for the field of cognitive geometry, which studies how humans and other animals understand and navigate the geometric properties of their environment. If Penrose’s ideas are correct, our ability to understand and manipulate geometric structures may be a fundamental aspect of consciousness, rooted in the quantum geometry of the brain itself.

The final conclusion of all this is rather alarming. For it suggests that we must seek a non-computable physical theory that reaches beyond every computable level of oracle machines (and perhaps beyond).

Roger Penrose, Shadows of the Mind: A Search for the Missing Science of Consciousness

Roger Penrose’s philosophy is deeply rooted in the Platonist view of reality, which posits that abstract mathematical forms and concepts exist in a realm of their own, independent of the physical world and human cognition. This “world of perfect forms” is a reference to Plato’s theory of Forms, which suggests that non-physical forms (or Ideas), and not the material world known to us through sensation, possess the highest and most fundamental kind of reality.

In Penrose’s view, this Platonic realm is not just an abstract mathematical playground, but it is the very blueprint of reality. The “perfect forms” he refers to are the mathematical structures and concepts that underpin the laws of physics and, by extension, all of physical reality. This is the “primary” world in Penrose’s tripartite division of reality, which also includes the physical world and the world of human consciousness. The physical world and the world of consciousness are “shadows” in the sense that they are manifestations or reflections of the underlying mathematical reality.

The physical world, according to Penrose, is a shadow in the sense that the laws of physics, which govern the behavior of the physical world, are themselves derived from the mathematical forms in the Platonic realm. Similarly, human consciousness is also a shadow, as Penrose believes that our ability to comprehend and manipulate mathematical concepts suggests a deep connection between the mind and the Platonic realm. This connection, he posits, could be rooted in quantum processes within the brain that are capable of interfacing with the geometric structures in the Platonic realm.

This perspective offers a profound and somewhat mystical view of reality, where the physical world we inhabit and our conscious experiences are but reflections of a deeper, mathematical reality. It’s a view that places mathematics not just as a tool for understanding the universe, but as the very fabric of reality itself.

In the grand scheme of things, Penrose’s work is a testament to the power of the human mind, to our ability to decipher the patterns of the universe, to bridge the gap between the physical and the mental, to find beauty in the complexity of the world around us. His work is a reminder that we are all explorers, journeying through the cosmos in search of understanding, guided by the light of knowledge and the compass of curiosity.

I imagine that whenever the mind perceives a mathematical idea, it makes contact with Plato’s world of mathematical concepts… When mathematicians communicate, this is made possible by each one having a direct route to truth, the consciousness of each being in a position to perceive mathematical truths directly, through the process of ‘seeing’.